Reviews

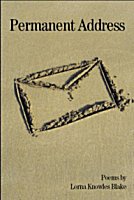

Permanent Address

by Lorna Knowles Blake

Permanent Address

Permanent Address

by Lorna Knowles Blake

Ashland Poetry Press, 2008; 67 pages; $14.95

ISBN 978-0-912592-61-9, Paper

http://www.ashland.edu/aupoetry

by Philip Miller

There is a garden at the center of many of the poems throughout Lorna Blake's resplendent new collection of poems, Permanent Address, providing a symbolic organization for the entire volume of poems. Before one finishes the collection, the place or situation of every poem—each new address Blake's narrator/protagonist examines—will resemble a kind of garden, having, of course, an actual location, as well.

Blake's real places can be almost anywhere: Riverside Park, a desert island, Quivett Creek, Paris, even Cuba where the narrator in "The Revolution Box" listens as "on the short wave radio, Fidél's voice drones on and on" and "Outside, the tamarind and mango trees let fall/their ripe and unused fruit." Often these places are the protagonist/narrator's new home or an old home she returns to by way of memory. Each poem's address is always as impermanent as a lost Eden, as permanent—in the mind—as the power of Eden's myths.

Early in the collection, Blake's garden emerges as a simple Eden of wish fulfillment, the title of one poem, which begins in "a spring of hope and mistrust." The narrator plants "vines and petunias" and awaits hummingbirds all summer. One finally appears:

… a hummingbird stalled

in the amazed summer air—hover and dart—

then vanished, swift as the instant just before waking, when

you get what you always wanted.

Attaining one's heart's desire, like "regaining" paradise, leads only to a fleeting moment, but also a captured one, an Eliot still moment like the scene in Blake's "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose," a delicately controlled pantoum about a John Singer Sargent painting:

… there is no before or after,

only a summer evening in the garden,

the perfect disappearing now of dusk

caught, as in a jar, held for a moment.

"An Evening Prayer," the very next poem in the collection, takes place in an autumn garden where the narrator observes "spent flowers curl into fat buds,/dry leaves float up from the ground, furling/into tight green cocoons of possibility." The "spent flowers" and "dry leaves" of this "fallen" garden provide fodder for a new spring; they resemble "cocoons of possibility," symbols of change-what will metamorphose into a future—and of new knowledge, like the kind latent in an autumn Eden, a kind once forbidden to its first inhabitants.

The possibilities offered by Blake's gardens are not the fleeting "perfect" moments of wish fulfillment, but their permanent memories. They are the amazing "notions" in her poem of the same name, a poem, which—it seems to me— condenses and crystallizes Blake's central themes, providing a miniature of the entire collection. The narrator visits a sewing shop which sells, of course, notions: "Just like Eve in the garden,/… [she] wanders through store aisles." What follows is splendid gathering of words for notions and other items that belong in the shop that sells them:

She's sees buttons, grommets,

pinking shears, needles, spools

of mercerized thread …..

Sees bolts of fabric, doesn't think

bias, cut. When the apple-shaped

pincushion catches her eye,

she doesn't yet think, heart, pierced.

Every word fits into the imaginative "garden" of the poem, "Notions" (with its central apple-shaped pincushion) as items born there, but, I must add, that also fit historically as well, as I remember each item and its name from my own grandmother's notions shop of the 1950s. Blake does all this in three beautifully modulated, four line stanzas. Indeed, throughout the collection, the measure and balance of her lines—in counterpoint with the slantness and varied textures of her language—fit her words often into stanzas, rhymed and unrhymed, including forms like the sonnet, sestina, and rondeau, with what seems effortless precision.

When we get to the title poem of Permanent Address, we already know that Blake's gardens are all versions of the imagination, poem after poem providing fresh varieties of Yeats and Marianne Moore's "imaginary gardens." The narrator sees further: "wherever home/was at the time; now//these are the houses/of photographs and/dreams, where I still see//a girl's room, a swing,/a crape myrtle tree." This is when "always sedulous, memory goes on/charting its atlas of imaginary//places-some radiant, some ruined-in mind." Of course, if memory is always innocent, it is also, in Lorna Blake's world, the location where the imagination (lost like Eden) can be found again.

In Blake's poem called "Eden," the narrator learns that the world of ordinary experience has come to her after a fortunate fall. The narrator in 'Eden" finds "a perfect world adjacent/to this one." But she also falls "again and again into desires sent/nightly to trouble my dreams, demanding their own worlds …." Eden is always "over there" where "the rain has always/just ended" and it "keeps expanding/ its boundaries" and "fruit awaits to be plucked," which she tells us succinctly at the end of the poem that she "may, someday" since all the "possibilities" of the garden still exist permanently in the imagination.

One of the "fruits" of the world that may be plucked (after a fortunate fall) is ordinary human love and, the possibility of relationship, as in Blake's poem, "After a Fight" when she

must make my way back,

and touch you lightly

so you will turn toward me

before the world bears down again

In "Autumn Argument" (which is written in three four-liners like "Notions" and uses "envelope" stanzas), Blake's narrator argues "I tell you—we love/the autumn leaves because they fall." In "Prothalamion," her narrator echoes Yeats: "Love will pitch its tent anywhere.," but also observes that love cannot survive or succeed without the imagination, without language—that only in a "house of words" do "you stand a chance, a fighting chance."

The pleasures and insights of Lorna Blake's Permanent Address are multitudinous, the variety of work generous, each poem deepening in value and meaning on each rereading. At times, the collection seems to discover and celebrate every implication and notion of the word "garden," which exists everywhere in Blake's work in its impermanent permanence, fallen yet resurrected; lost but regained; symbol of the imagination while also being captured by it. Near the end of the collection (after we realize just how many kinds of poems Blake can write), she provides still new varieties, including a sequence, "Proverbs from Hell," each poem in a different form and with its title taken from one of William Blake's proverbs. This suggests that Lorna Blake takes her aesthetic from William, whose work, like hers, shares an extraordinary immediacy of dramatic conflict and achievement of metaphor. She seems to be referring to the aspirations of all poets in "No bird soars too high, if he soars on his own wings" (with its allusion to Icarus):

But in every generation, it seems, they try

remembering not the fall, but the heady

lift of flight…

They risk the fearful plummet to earth or sea

and stunned like garden birds who cannot see

the plate glass air of windows, unsteady,

numb with yearning, they rise again to fly.

Philip Miller's recent poetry has or will appear in many magazines and journals including The Cape Rock, The Seventh Quarry (Wales), Poetry Midwest, Birmingham Poetry Review, Gargoyle, and Seam (UK). His chapbook, Fathers' Day, won Ledge Press' 1995 chapbook award. Of his five collections, the most recent is Branches Snapping (Helicon Nine Editions). His sixth book, The Casablanca Fan, is due this year from Unholy Day Press. He lives in Mount Union, PA where he edits The Same and is a contributing editor of Big City Lit.